January 2014

Greatham Creek is a tributary of the river Tees, not really flowing into the river, but forming part of the delta, and joining the estuary at Seal Sands beyond Seaton Snook on the south side of Hartlepool.

I used to cycle there in the late 60s and early 70s when there was the remnant of a thriving houseboat community.

Houseboat, Greatham Creek c.1972.

Surrounding that community was an RSPB nature reserve, set up to protect the only feeding habitat between Lindisfarne to the north, and the Humber estuary to the south. It attracts many species of bird, particularly in winter.

Jetty, Greatham Creek c.1972.

This flat land is strewn with channels of brackish water, marsh samphire, springy turf and juncus; and finally, before the stretch of sea, sand dunes of blue and green marram grass with orchids, genista and sea buckthorn.

Visitors of the human kind are sparse, and it is a place of peace, if not calm – it was my place to escape to.

I traipsed the turf and squelched the mudflat, collecting things that nobody in Hartlepool called ‘objets trouve’.

I listened to the birds, sometimes I picked samphire for tea, and I enjoyed whatever circumstance might offer me.

This was my Narnia – a four-mile cycle ride was the wardrobe that gave me entrance.

After several trips, I began to feel that circumstantial offerings were not quite enough for me. I had an urge to make more of my visits; I needed to record in some way, what was important about this place. So, I started to bring my sketchpad and pencils with me, because who was going to believe my Narnia adventure if I didn’t record it?

The remnants of the houseboat community were a visual stimulation to me – they were packed with lines and textures, shapes and tones, all modified by the effects of winds and big tidal washes.

At that time I sketched without confidence.

My drawings were as thin as the paper they were drawn on, but I needed to do them, and my Narnia remained personal, because I never went public with the sketches; there wasn’t anyone to show them to.

Sketchbook entries from my youth.

I re-visited this place after the community had disappeared, and each time I still felt the urge to draw it, and only recently did I consider it not too late to do so.

So, why shouldn’t I draw it now, having gained more confidence to do so, as well as the visual language to put something together? I still had some of the sketches, I had a lot of photographs, and I still had a strong urge to express the place – the drawings were in me.

I returned again, over 40 years on. The place was devoid of the structures, but other, perhaps less physical elements were still present. The dimension of time was not a barrier, and I began to draw what had been.

Houseboat at Greatham creek, 1972. Mixed media. Drawn 2014

Mac’s Island, Greatham Creek, 1972. Mixed media. Drawn 2014

I always remember there being a wind at Greatham Creek – from a breeze to a fierce gale; a wind carrying the smell of salt, and the sustained warble of skylarks in early summer.

In winter I remember the ‘kleep, kleep’ of the oystercatchers, and showers of squadron-like knots.

There was also the industry alongside the river Tees itself, the thud of heavy steel and machinery, muted by distance.

The six newly constructed, high concrete towers of the shell of a nuclear power station were a sign of what was to come.

It was here, wanting some cash so that I could add to my Joni Mitchell album collection, that I took a job for a couple of days as a chain boy, for a civil engineer. Clad in my thin school parka, I tediously hung on to a measuring pole, in the January sleet and high winds, whilst he took readings through his theodolite. In doing so, I had become part of the process that lead to the devastating change of much of this environment, where I felt such a close affinity.

That community at Greatham Creek has long been swept away, the houseboats have gone, many of them mysteriously burned down. Now there is a high bund wall, it is long and straight, and covered only in grass. Like a main road through a dull housing estate, it’s the sort of place that seems to take an awful long time to walk through; it holds no interest. Within its secured boundaries, there is an oil terminal.

It is so gratifying to know that the devastation of this rich, vibrant, creative and frugal community, means that the likes of Lord Howell of Guildford can fill up their cars with petrol knowing that the view from their own back gardens will not be disturbed.

Large chemical works have been constructed along the course of the river Tees itself, and I now consider both these areas to be somewhat out of bounds to me as an artist – the area where the oil terminal stands, because it is now as visually dull as the muddy waters of the creek itself.

Oil pipes, Seal Sands, c.1995.

And there is the river, which does still hold a visual interest – albeit of a new and very different kind – it now appears to feel threatened by my presence, evidenced by my being moved on by security guards at Philips petroleum when they spotted me sketching pipelines via their CCTV screens.

In one of my summer student vacations I worked as a security guard at Philips petroleum, and I nearly died of boredom; so this incident may well have been the highlight of their Sunday, and it is reassuring to know that they are saving the nation from potential sketching terrorists.

In spite of bulldozers and bullies, Greatham Creek still holds a great interest and a fascination to me as a painter. Alongside these chemical giants, smaller industries operated, with their rusting machinery and their corroding corrugated iron buildings, nestling into tall grasses and wind sculpted, stunted trees. this is what I drew and painted.

Sea buckthorn and shed, Seaton Snook, Ink drawing. 1995.

Sketchbook entries for Seaton Snook, Crayon, charcoal and pastel. 1995.

.Seaton Snook is an area of dune land lying cheek-by-jowl with Greatham Creek. They are linked together by a road romantically known as the Zinc Works road. It begins with a curve that entices you towards the dunes. At the end of a dry summer the grasses take on ochre colourings; road edges of grit and dust are ambiguous, and there are isolated, sculpted shrubs.

The road has now been re-surfaced and contained by a rigid 4 inch concrete kerb – this presumably is ‘planning gain’, a condition of the new chemical works development at the end of the road, emitting odours that make one feel sick in the pit of the stomach. The softness of the landscape has disappeared; it has been imposed upon, suburbanised.

I am not objecting to progress here; I am downhearted that these kind of insensitive changes should be perceived as being progress.

Am I the only person who prefers an ambiguous road edge in such a situation of relatively infrequent use?

Zinc Works Road. Pastel drawing.1995

I feel alone in expressing this – am I the nutter going on about kerbs and grit? To many folk, I would be; but I do wonder how many people have really looked and thought about it – none of the braying councillors or planners, I’ll bet.

Both Seaton Snook and Greatham Creek are places that belong to the few. People are few and far between. It is an exposed area of marshlands and sand dunes with industry. It is strong and not always comfortable, but full of surprise and interest.

Rusting surfaces of a steel oil tank and a corrugated iron shed. 1998.

The industry soon acquires a patina, lending itself to a rich abundance of textures – these salt encrusted sheds have now replaced and lost their rich texture – but nature will start again in creating another.

There is a rich abundance of visually stimulating material

Patterns left by the tide – fine sea coal. 2003.

Seaton Snook. 2003.

The dunes and the beach are shared. No longer by the seacoal gatherers, because there is very little seacoal left to gather, but the dog walkers are there, the odd runner, a handful of bird watchers, the few who have learned to love the place, and the artists, well there’s me (if there’s anybody else out there I’d love to know).

The light is often so fresh that it lightens the step – there is a lot of space here; large skies and open water – its emptiness is one of its great attractions, but being largely devoid of human activity is a mystery to me – especially when you no longer have the inconvenience of driving down a road with potholes and an ambiguous edge to get there

Sketchbook entries of ‘The Blue Lagoon’. 2012.

The rich flora of the dunes. Seaton Snook. 2013.

As a child, the dunes were an exciting place – perfect for re-enacting heroic deeds from the second World War.

They are still a joy, but not as a theatre to gun down imaginary enemy soldiers – now I appreciate the tall grasses for other reasons; I like their movement, their texture and their colour, so I draw them.

Coltsfoot growing behind the dunes (detail). Pastel drawing. 1995.

Summer grasses and wild flowers behind the dunes (detail). Pastel drawing. 1995.

The dunes are like an armchair of memory foam – for lying in and watching the life of the river and its industries across the estuary. This inlet, by the North Gare, is known locally as ‘The Blue Lagoon’.

The shipping lane is constantly busy, and the steelworks at Redcar, an arms length attraction.

Plumes of white steam are thrust into the sky at the quenching of a coke oven; the sky glows orange at the tapping of a furnace, there are thuds and screeches of steel and trains. I can enjoy these, they are the region’s raison d’être, but there is also, on a bad day, the gut-wrenching smell of chemical works.

It is not possible to accurately describe what a place is like without qualifying the time and conditions; even your own mood affects the way in which you perceive a place.

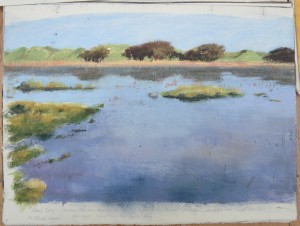

It is behind the dunes where I returned to paint more recently. This hinterland is crossed with rivulets and dotted with ponds, reflecting a moving sky, a shifting light and changing colour

It is low, hummocky land with the sounds of associated birds and the not-so-distant sea; there is the smell of salt (but sometimes chemicals), in the wind.

It is a fine environment for private thoughts and reflection.

Sketchbook entries. Pastel. 2012.

Rivulet at Seaton Snook. Mixed media. 2011

Passing storm, Seaton Snook. Mixed media. 2011.

This is a small, yet enormous, area that has had a considerable influence on me.

There are other parts of County Durham and North Yorkshire, that have also had such an influence, and each time I return home I prepare myself to look closely at them.